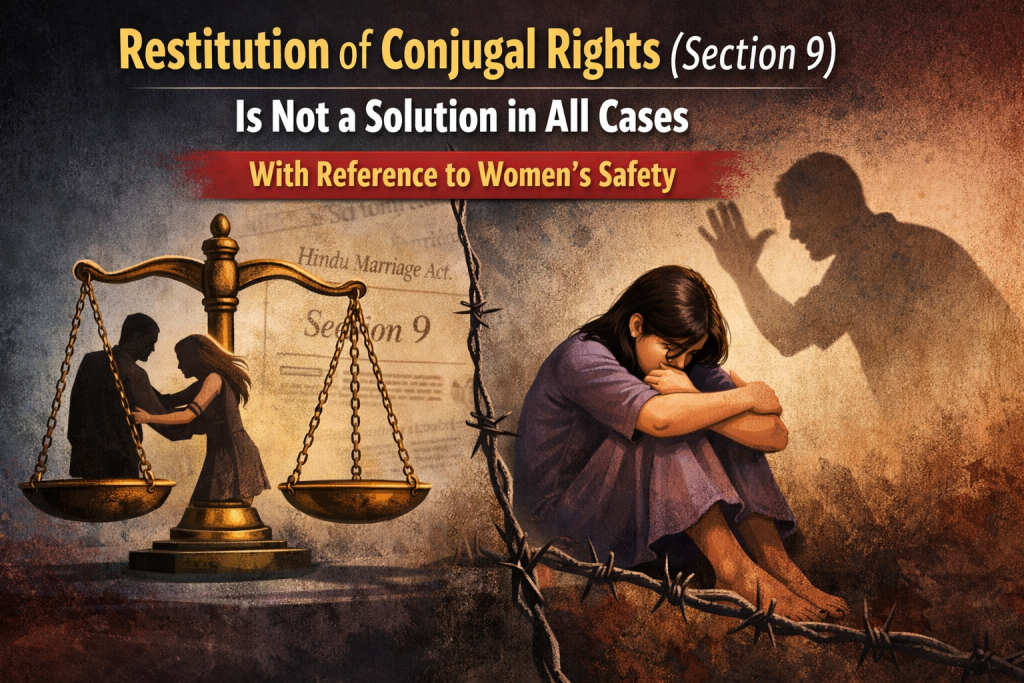

The Section 9 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 expressly provides for Restitution of Conjugal Rights (RCR). As per this provision, if either spouse has withdrawn from the society of the other without any reasonable cause, the aggrieved spouse can approach the court seeking a decree compelling the other to cohabit again in relationship. It is important to note that the basic objective of section 9 is to preserve marriage but the practical consequences, especially in the case of women, invariably reveals that RCR is not always a safe, effective, or just solution.

Basically we need to understand the assumption laid down in section 9 marriage which could be problematic as it assumes that harmony can be restored through legal compulsion, and withdrawal is usually an irrational act needing correction. However, in many cases women leave the marital home due to various reasons such as domestic violence, emotional or psychological abuse, dowry harassment, marital rape or coercive control, threats from in-laws, unsafe living conditions, etc. Now for such women, a court order forcing them to return can place them in great danger and violate their rights.

Women’s Safety and Autonomy

The provision does not adequately address the reasons behind a woman’s withdrawal. Even if she fears domestic abuse when it comes to RCR she must prove “reasonable cause” before court, and this can be traumatic, lengthy, expensive, requiring evidence which victims often cannot produce. Thus, the burden wholly shifts to the woman to justify her own safety concerns, undermining autonomy and bodily integrity.

Potential Tool for Coercion

Essentially many women’s rights groups and courts have time and again recognised that RCR can be misused by husbands to counter wives’ claims of cruelty or maintenance or can be used to pressure women into withdrawing complaints, it can also be a force negotiations in divorce or maintenance matters which can be weaponised to show the woman as “deserting” the marriage and weaken her legal position. Thus, Section 9 often becomes a litigation tactic rather than a genuine attempt to save a marriage.

Supreme Court Commentary and Criticism

The Hon’ble Supreme Court has repeatedly raised constitutional concerns regarding section 9 in case of T. Sareetha v. T. Venkata Subbaiah,1983 AP High Court held that section 9 unconstitutional as it violated privacy and bodily autonomy especially of women. In the case Saroj Rani v. Sudarshan Kumar, 1984, supreme court recognised that the decree cannot be enforced physically. Then in the case of Joseph Shine (2018) and KS Puttaswamy (2017) judgments the court strongly emphasised individual autonomy, raising fresh doubts about the compatibility of RCR with the right to privacy and dignity.

In this regard many scholars argue that after privacy became a fundamental right, RCR has become constitutionally vulnerable as it does not provide real marital solution, since marriage breakdown is often rooted in emotional disconnect, violence, financial insecurity, major patriarchal control and lack of mutual respect.

RCR does not fix abusive behaviour, ensure safety, encourage counselling, address psychological trauma, provide financial relief, instead focuses on formal cohabitation, ignoring relationship realities.

Women’s safety must take priority in cases involving domestic violence (Section 498A), dowry issues, child safety concerns, threats of familial pressure. Ordering a woman to return to the marital home may expose her to physical harm, mental cruelty, retaliation for approaching the court, social pressure to “adjust”.

This contradicts India’s obligations under:

- CEDAW (Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women)

- Domestic Violence Act, 2005.

- Principles of dignity and safety under Article 21 of the Constitution.

RCR can invariably undermine women’s financial relief claims as a decree of RCR can be used to argue:

- The woman is unwilling to live with her husband → which can reduce maintenance

- She is “deserting” the marriage → affecting divorce outcomes

- She must return before being eligible for support

This has severe economic consequences, particularly for women who left due to abuse. While Section 9 aims to preserve marriages, it is not appropriate in cases involving women’s safety. A legal provision which invariably compels cohabitation and that too without addressing underlying problems in marriage can turn out to be dangerous for victims and undermine autonomy and can enable coercion. It is essential to understand that reform is necessary, through either limiting RCR strictly or replacing it with mediation-based remedies or abolishing it in line with global trends rejecting forced cohabitation. It is important that women’s safety and dignity remain central and no legal provision should compel a person to return to an unsafe environment.